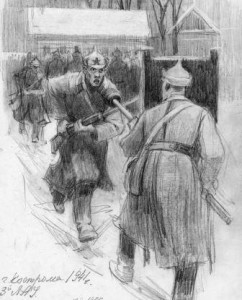

All the years after the war Sergey Babkov continued to re-live the memories of the war years. They came to him in his dreams, he revives them in drawings and paintings. This drawing is made upon his impressions of the training in the Leningrad Artillery School. In his diaries the artist wrote:

“I should not even try to tell about our six-month long learning period – I can go for ever. I’ll say only that the conditions were harsh, and the discipline was harsh. At first it seemed that we were getting prepared for bayonet fighting, rather than gun-firing fighting. In addition, the School authorities were infinitely changing our specialties. Be as it may, the School tempered and embittered us, whilst teaching us to obey orders and give orders. In general, it built in us the foundations, without which an army cannot exist and be viable. We graduated in the ranks of lieutenant and were sent to the front … “

“I remember the first time I stood with the platoon of howitzer battery control lined up in front of me, which I had to command. They were experienced soldiers, who came from the western borders through war-front battles, cured by water, fire and copper pipes, everyone was older than me… I can only imagine what they thought while looking at the me, a spring chicken with lieutenant cubes in uniform buttonholes, who should give them orders!

Although I think my baptism by fire began somewhat earlier, during a dinner with the battery commander, he poured me a glass of vodka and I drank it pretending that it was ordinary for me. Very quickly I felt that my head turned into a piece of wood … So I stood and looked at my subordinates, armed with assault rifles and carbines, with weather-beaten, brick-coloured faces, and felt that I have nothing to say… I said my greetings and dissmissed them. After that I familiarised myself with the (household of the) platoon…., visited an observation post, which was not at all as we were taught in school – and was just a hole. The first explosions of the German mines, whistling bullets, and most importantly – the front without trenches, but with separate foxholes and wandering lonely figures … “

“The daily ration of a soldier was reduced to two pieces of dry bread, soup with lentils, 100 grams of vodka and a piece of herring. This ration was sometimes topped up by half-rotten potatoes, the leftovers of the 1941 harvest, of which we baked malleable gray pancakes on sheets of iron. The solitary figures of such soldiers I saw for the first time at the front. Naturally, as a result of such a diet, people quickly became dystrophic…

…When you are in the state of dystrophy you have no sense of danger. In my platoon our Deputy Commander was terribly afraid of the artillery attacks – a burly fellow, a well-trained Sergeant. He always waited for the end of the distribution of the lentil soup and ate the thick part at the bottom of the thermos, which was brought from the battery to us at the observation post, and that’s how he kept his strength and youthful appearance. His fear of the shells and mines was not in vain. Soon he was killed by a shell fragment, which hit him in the temple. His death was the first incident of foreboding death, which I later witnessed more than once. Now I am convinced that there is a category of people with a stronger sense of danger, and they come out of any situation intact – this is the so-called ‘soldier’s luck’…»